Training for Strength: A Beginner’s Guide

Note: this article pairs nicely with our podcast episode on Heavy-Light-Medium found HERE

One of the questions I get asked most frequently by new (and experienced) athletes is “how do I get stronger?” While terms like “strength” and “stronger” can often trigger a cascade of physiological mansplaining, I tend to assume that the athlete is looking for strategies to progressively add weight to the barbell.

Previously, I posted a discussion on the fundamental truths of tactical training to serve as a stepping-off point for an ongoing series of articles diving into how to train for different goals effectively. With that in mind, the intent today is to conduct a deep dive into one of my favorite strategies for programming strength: the Heavy-Light-Medium construct.

Disclaimer

I will say at the outset that there are myriad ways to train for strength. Depending on your background, preference, sphere of influence, etc. you may have heard of terms such as Westside, Starting Strength, Smolov, German Volume Training, or any of the other untold dozens of approaches out there. I am not here to say that any of these are better or worse than any other; rather, in my own experience working in the tactical human performance space, the Heavy-Light-Medium framework has provided maximum flexibility and adaptability to just about every athlete I’ve ever worked with.

Heavy-Light-Medium Overview

I was first exposed to HLM by a longtime influence of mine, Andy Baker. He, in turn, was introduced to the concept by an OG strength coach from the 1970s, Bill Starr, in his work The Strongest Shall Survive, which was inspired by an even earlier strength pioneer in the 1930s, Mark Berry. Needless to say, the HLM framework has a track record of success.

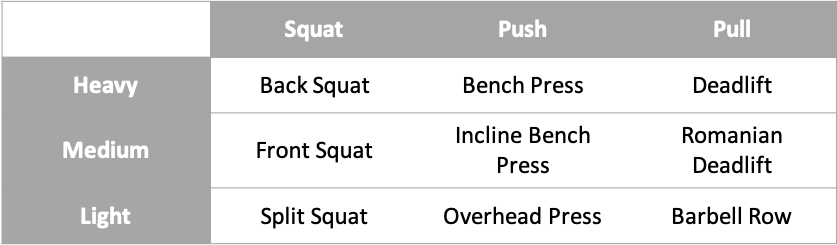

The most basic version of HLM involves three days of lifting in a week with a rotating list of exercises that focus on Squatting, Pushing, and Pulling. Each of the three movement patterns receives three exposures: a heavy exposure, a medium exposure, and a light exposure. If you’re keeping up with the math, that gives us nine exercises in a week with three exercises each day. Perhaps a graph will help illustrate this concept:

Three days of lifting with three exercises on each day

You’ll notice that although the framework is called “Heavy-Light-Medium,” the order of the exercises on a given day actually goes Heavy-Medium-Light in keeping with the tried and true principles of exercise order within a session. Basically, as you fatigue from the beginning of a session to the end, it makes sense to inject exercises that become easier/less taxing as you go.

Diving In

Now that we have the 10,000ft view sorted, let’s dive into exercise selection and weekly ordering. I mentioned earlier that we’re focusing on three movement patterns: squatting, pushing, and pulling. I also said that each of those three patterns receives three exposures: heavy, medium, and light. With that in mind, we reach our first decision point: do we want to hit all three exercises for a given movement pattern on a single day (i.e. do all the squatting movements on Monday) or do we want to spread them throughout the week? For my money, I’d opt for the latter and for the purposes of this article will focus on that approach. You’re welcome to torture yourself with the other option if you’d rather.

Exercise Selection

I could write a million articles on the intricacies of exercise selection, and undoubtedly in the future, we will publish more than one piece diving into the topic. We’ll keep things simple for today's discussion and focus on the barbell. I’ll add a few comments throughout for folks interested in dumbbells or other variations. Still, my hope is that by simply illustrating the concepts, the discerning athlete or coach will be able to find ways to make it their own. Something about cooks versus chefs…

I’ll use another chart here to help explain.

Simple barbell movements to fill out out exercise selection grid

As you work from heaviest variation to lightest, you should be able to easily see that the maximal loading for each of these movements sort of nicely “forces” them into the heavy, medium, and light categories. For example, you’d be hard-pressed to find an athlete who can overhead press more than they can bench press; thus, it makes sense that the heavy Push option would be the bench press, while the light Push option would be the press.

For the dumbbell crowd, one could easily start to introduce more unilateral/dumbbell-type loading towards the lighter end of the spectrum. For example, I might swap out the Overhead Press for a Seated DB Press, or the Barbell Row for a Single Arm DB Row. As you might imagine, the opportunities are endless.

I will pause for a moment to mention that there are versions of the HLM construct that use the same movement for all three loading options on a given movement pattern (i.e. heavy back squat, medium back squat, light back squat). To do this effectively, the coach will use percentage drop-offs. For example, the medium squat might be 5-10% lighter than the heavy squat, and the light squat might be 5-10% lighter than that. I would make the case that this is more of a “powerlifting-specific” approach and, while effective, is somewhat limiting in terms of athlete enjoyment.

Setting Up Your Week

By now we have discussed the overarching structure of HLM as well as how to select the exercises you’d like to work on for a given phase of training. The next step is how to actually set up a week. Once that’s taken care of, we’ll touch briefly on reps and sets using a sample training day.

It is here that the Heavy-Light-Medium construct lives up to its name. When you hit the heavy variation of a movement pattern, it makes sense that you might experience a considerable amount of fatigue. The next logical step, then, would be to hit a light variation of that same movement pattern on the following training day. Assuming that fatigue has dissipated following the light exposure, the next training day will see that same movement pattern via the medium loading option.

Another chart:

A weekly layout for the squat pattern following the heavy-light-medium ordering

I’ve illustrated the Squat, but it should be pretty easy to fill in the same structure for the Push and the Pull. If Wednesday is your heavy Push, Friday (the next training day) would be the light Push and the following Monday would serve as the medium option. And the world spins madly on.

A Single Training Day

Let’s zoom in one level further and examine a singular training day. Because we’ve spent so much time using the squat as our example, we’ll use Monday (our Heavy Squat day) as the example session. Bear with me here: because Wednesday is our Heavy Push day, our Squat day will include the Medium Push option (Incline Bench Press). Similarly, because Friday is our Heavy Pull, Monday will use our Light Pull option (Barbell Row). All told, the Monday strength session will include the following exercises: Back Squat, Incline Bench Press, and Barbell Row.

When it comes to selecting reps and sets, I’m going to try and skilfully navigate a veritable minefield of rabbit holes and focus only on absolute basics. I assure you we’ll dive into each and every one of these rabbit holes in future articles, but for now, let’s keep it simple.

Exercise 1: Back Squat

Because the squat is the focus of the day, and strength is the focus of the phase, I typically opt for a low- to mid-rep range that will promote heavier loading without undue metabolic fatigue. 3-5 reps, for me, is the perfect blend. As far as intensity goes, for a beginner-ish athlete I’ll usually opt for an RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) around 7-8, meaning that on a scale of 1-10, the subjective difficulty is “hard” but not “impossible.” I realize I threw some new terms at you here (RPE, rep ranges, etc.). Remember what we said about rabbit holes?

Exercise 2: Incline Bench Press

Our second exercise allows for a slightly higher rep range to promote some additional muscle growth, as well as a slightly higher RPE putting us closer to true failure. Why? The nature of the Medium load option is such that you have a lower risk of injury due to the fact that the movement itself is somewhat limiting. I can load a back squat to high heaven and let an athlete absolutely crush themselves, but with something like an incline bench press technical failure tends to happen before true muscular failure. I like an 8-10 rep range with an RPE of 8-9 here.

Exercise 3: Barbell Row

The third exercise of the day, for me, falls squarely in the “accessory work” category. With that in mind, both intensity and rep range can skew a bit higher for the same reasons we discussed with Exercise 2. 10-12 or even 12-15 reps is doable, and RPE can hang out at the 9-10 range provided that reps are executed with intent and technical proficiency.

Oh, look! Another chart!

Consider this a basic example. The more developed an athlete and the more individualized a program, the more these might change

I didn’t on Sets yet, and that was intentional. With just about every athlete I work with, we’ll start with three sets on all exercises. I find that anything less than that feels like a wash, and anything over that starts to take up too much time and can create boredom. If, after a number of phases/exposures, the athlete’s adaptation is signaling that more volume is appropriate, more sets can be added.

Summary

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: there are myriad ways to train for strength. The Heavy-Light-Medium framework is merely one option of many, though my hope is that with the examples above you can start to see the potential for creative flexibility that HLM provides. In future articles, we’ll dive deeper into some of the concepts I’ve touched on here: rate of perceived exertion, rep ranges, accessory movements, creating effective supersets, how to account for hybrid training demands, etc.

To give you a very easy checklist of how to get started with HLM, consider the following:

Set up the 3x3 grid and choose your exercises. A heavy, medium, and light variation for each of the three movement patterns

Set up another 3x3 grid to lay out your week. Heavy exposure first, then Medium, then Light.

Zoom in on each training day and input your goal rep ranges and ideal intensity levels. I prefer to use RPE here, but you could use percentages or even prescribed weights (you’d be wrong, but we’ll get into that later #winkyface)

Complete a week of training and take internal notes on what works and what doesn’t.

Modify, modify, modify

I did not create the Heavy-Light-Medium framework, and I would encourage you to dive deeper into the writings of Andy Baker, Bill Starr, and others to learn more than I could ever hope to contain in a single blog post.

Happy lifting!