What Your Wearable Readiness Score is Telling You

This is a guest blog post submitted by a member of Leg Tuck Nation. The content represents their own views and opinions, with edits made only for grammar, clarity, etc. If you are interested in submitting your own content for consideration, click here.

Introduction

What does that readiness number on your fancy watch really mean? The popularity of biometric tracking devices or wearables has exploded. Everyone now has access to the same technology and data sports scientists use to monitor professional athletes. With this access comes the ability to make more informed decisions about training, if you know what you are looking at and understand what goes into all the data. The 1 to 100 scale most fitness trackers use for their readiness number are proprietary algorithms, primarily made up of Heart Rate Variability, sleep, and activity measures.

Understanding Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a measure of the variation in time between successive heartbeats, which is controlled by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Unlike a simple heart rate measurement, HRV provides insight into the balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the nervous system. Higher HRV generally indicates better autonomic balance and recovery, while lower HRV may suggest stress, fatigue, or insufficient recovery (Christiani et al., 2021).

HRV is particularly useful for monitoring readiness because it reflects the body’s ability to adapt to stress. Studies have shown that HRV can be used to track changes in cardiovascular fitness, monitor recovery from training, and predict performance outcomes (Flatt et al., 2021). Military personnel can use HRV to determine when to push harder in training and when to prioritize recovery.

The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System in HRV

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) consists of two main branches:

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): Often referred to as the "fight or flight" system, the SNS prepares the body for action by increasing heart rate, redirecting blood flow to muscles, and elevating stress hormone levels.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS): Known as the "rest and digest" system, the PNS promotes relaxation, recovery, and energy conservation by slowing the heart rate and facilitating tissue repair.

HRV serves as a window into the balance between these two systems. A high HRV indicates strong parasympathetic activity, suggesting good recovery, while a low HRV reflects heightened sympathetic dominance, which may indicate stress, fatigue, or overtraining. For military personnel, this data can be invaluable in assessing readiness for strenuous activity.

Dr. Andrew Flatt’s Work on HRV and Its Application to Military Training

Dr. Andrew Flatt has conducted extensive research on HRV in elite athletes, including college football players, demonstrating how HRV can guide training decisions. In his studies, Flatt monitored players’ HRV trends to determine whether they were recovered or experiencing accumulated fatigue. When daily HRV measures were consistently higher athletes were able to handle greater training loads, whereas multiple low daily HRV readings in a short period of time indicated the need for reduced intensity or additional recovery measures (Flatt et al., 2021).

Military professionals can apply these same principles. By tracking HRV each morning or night, tactical athletes can identify patterns and adjust training intensity, sleep, hydration, and nutrition. For example, if a soldier’s daily HRV reading is consistently low following multiple days of intense training, this could signal the need for a de-load period or additional recovery interventions often increased sleep.

In addition to overall HRV trends, specific metrics are commonly used to assess recovery and readiness. One of the most popular time-domain measures is the Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences (RMSSD), which is particularly sensitive to parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) activity. Typical RMSSD values in healthy, moderately trained individuals range from 20 to 60 ms, though endurance-trained athletes can exceed this range, sometimes reaching 50–80 ms or more. Since RMSSD values can be skewed by outliers, practitioners can use the natural logarithm of RMSSD (LnRMSSD) to stabilize the data and facilitate comparisons across individuals and training sessions. A typical LnRMSSD value might fall between 2.5 and 4.0, though individual baselines can vary widely. Some fitness tracking devices take the LnRMSSD value multiply it by 20 and give you a readiness number.

Sleep Measures and Their Role in Recovery

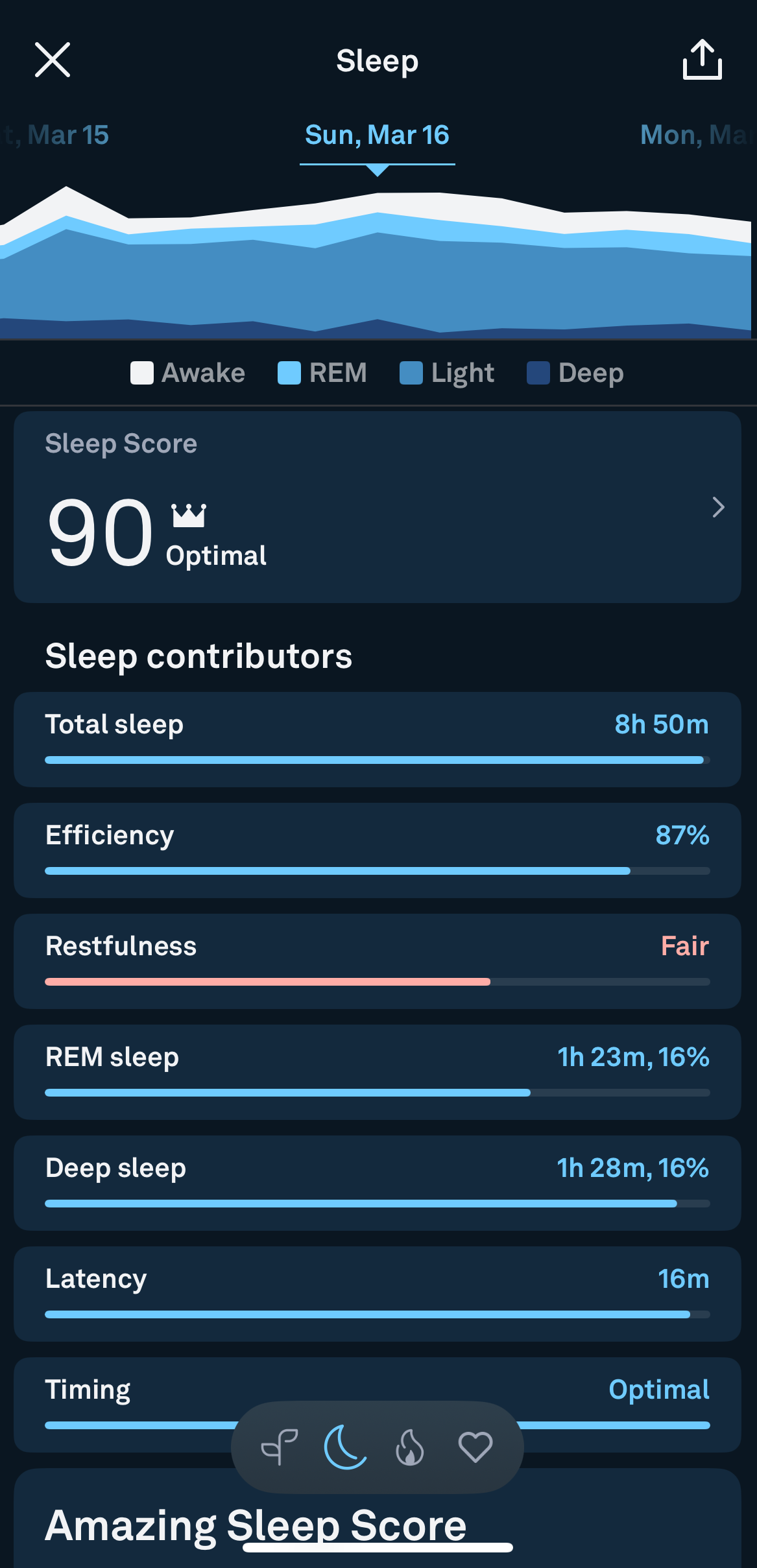

Sleep is one of the most critical factors in recovery, influencing cognitive function, physical performance, and overall well-being. Several sleep metrics provide deeper insights into recovery status:

Sleep Timing: Monitors your bedtime and wake time to help you align your sleep schedule with your natural circadian rhythm, promoting optimal recovery, hormonal balance, and overall performance.

Deep Sleep: This stage is essential for physical restoration, muscle repair, and hormone release. It is particularly important for tactical athletes due to its role in muscle recovery and immune system support (Walker, 2017).

REM Sleep: This phase is crucial for cognitive recovery, memory consolidation, and emotional processing. Military personnel undergoing intense training or operational stress benefit from adequate REM sleep to maintain mental resilience (Stickgold, 2005).

Sleep Latency: The time it takes to transition from wakefulness to sleep. Prolonged sleep latency can indicate heightened stress or poor sleep hygiene, which may impact recovery (Walker, 2017).

Tracking these sleep variables alongside HRV provides a more comprehensive picture of recovery. For instance, a soldier may have a high HRV but insufficient deep sleep, indicating incomplete physical recovery despite autonomic balance. Conversely, poor sleep quality combined with low HRV suggests accumulated fatigue and a need for restorative interventions. By monitoring both HRV and sleep metrics, military professionals can make informed decisions about training loads, rest periods, and recovery strategies.

The Limitations of Recovery Scores (e.g., WHOOP, Oura)

Wearable technology such as WHOOP and Oura Ring have popularized the concept of a "recovery score" a single-number representation of readiness based on HRV, sleep quality, and other proprietary metrics. While these tools provide useful insights, a single score on a scale from 1-100 oversimplifies recovery. Many factors influence recovery, including nutrition, hydration, psychological stress, and previous training loads, which may not be fully accounted for in an algorithm-generated score.

Additionally, HRV fluctuates daily due to multiple variables such as caffeine intake, hydration levels, and even emotional stress. A low recovery score on a given day does not necessarily mean an individual is unfit for training. Rather, it should be used in conjunction with subjective measures such as perceived recovery and physical readiness.

Perceived Recovery vs. Measured Recovery

One of the most debated topics in recovery science is the relationship between subjective (perceived) recovery and objective (measured) recovery. Some studies suggest that perceived recovery can be just as effective as biometric tracking in predicting performance and fatigue levels.

For example, Laurent et al. (2011) found that subjective measures, such as an athlete’s self-reported fatigue and soreness levels, correlated well with HRV and other physiological recovery markers. Similarly, McLean et al. (2010) demonstrated that athletes who felt well-recovered generally performed better, regardless of what their biometric data indicated. This suggests that military personnel should combine both objective metrics (e.g., HRV, sleep tracking) with self-assessment tools such as mood questionnaires and readiness scales to make well-rounded training decisions.

Practical Application for Military Training

To effectively implement HRV, sleep tracking, and other biomarkers into military recovery strategies, tactical professionals should consider the following steps:

Daily HRV Monitoring: Track HRV trends rather than focusing on single-day values. This helps identify patterns and adjust training intensity accordingly.

Sleep Optimization: Use wearable technology to assess sleep duration and quality, emphasizing consistency and deep sleep to enhance recovery.

Self-Assessment: Combine biometric data with perceived recovery scales, noting energy levels, soreness, and mental readiness.

Adaptive Training Plans: Adjust training based on recovery markers. If HRV is low for multiple days in a short time span, consider a lighter training load or additional recovery strategies.

Hydration and Nutrition: Recognize the role of hydration and nutrition in recovery, ensuring adequate intake of electrolytes, carbohydrates, and protein.

Mental Stress Management: Incorporate mindfulness, breathing techniques, or decompression strategies to balance sympathetic and parasympathetic activity.

Conclusion

Incorporating HRV, sleep tracking, and other biomarkers into military training provides a data-driven approach to recovery, optimizing performance while reducing injury risk. While tools like WHOOP and Oura offer valuable insights, they should be used alongside subjective measures of recovery for a comprehensive approach. By applying HRV principles as seen in Dr. Andrew Flatt’s work with athletes, military professionals can tailor their training and recovery strategies to maintain peak readiness for operational demands.

Sources

Christiani M, Grosicki GJ, Flatt AA. Cardiac-autonomic and hemodynamic responses to a hypertonic, sugar-sweetened sports beverage in physically active men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021 Oct;46(10):1189-1195. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2021-0138. Epub 2021 Mar 24. PMID: 33761293. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/apnm-2021-0138

Flatt, Andrew & Allen, Jeff & Keith, Clay & Martinez, Matthew & Esco, Michael. (2021). Season-Long Heart-Rate Variability Tracking Reveals Autonomic Imbalance in American College Football Players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 16. 10.1123/ijspp.2020-0801. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34039770/

Laurent, C. Matthew, et al. "A Practical Approach to Monitoring Recovery: Development of a Perceived Recovery Status Scale." Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 25, no. 3, 2011, pp. 620-628. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20581704/

McLean, Blake D., et al. "Neuromuscular, Endocrine, and Perceptual Fatigue Responses During Different Length Between-Match Microcycles in Professional Rugby League Players." International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, vol. 5, no. 3, 2010, pp. 367-383. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20861526/

Stickgold, Robert. "Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation." Nature, vol. 437, 2005, pp. 1272-1278. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature04286

Walker, Matthew P. Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner, 2017.)

Mark A. Christiani is a Tactical Strength, and Special Operations Army Veteran. He has human performance experience in the worksite wellness, collegiate and tactical settings. Mark holds a Master of Science in Sports Medicine from Georgia Southern University and several certifications, including CSCS and RSCC. Currently, he serves as an on-site Human Performance Specialist with the US Army Reserves. Mark's extensive background in research, coaching, and injury rehabilitation underscores his commitment to advancing the field of sports science and human performance.