Double Progression for Strength Training

A Primer on Getting Strong Using RPE and Rep Ranges

It should come as no surprise at this point that “autoregulation” is a tool that I use almost exclusively when it comes to training athletes, tactical or otherwise. Given the inescapable realities of the tactical athlete’s environment, there really is no other way to effectively manage training than to put strategies into place that can account for daily fluctuations in readiness.

With that being said, it may come as a surprise that for the longest time, I could not crack the nut on how to actually progress an autoregulated strength training program from one week to the next. Sure, programming 3x5 at an RPE of 8 made plenty of sense for a single training session, but how do I make that session progress if I need the athlete to pursue absolute strength? Do I increase the RPE? Isn’t that just making it harder without actually pushing the stimulus? Do I decrease reps to increase intensity? Maybe…but shouldn’t RPE do something to? As is my way, I chewed on this problem for way longer than I should have before realizing that the answer was right in front of me all along…and it was dead simple.

Rep Ranges and RPE: Two Peas in a Pod

There are two pieces to the double progression model that you need to understand in order for any of this to make sense: RPE (rate of perceived exertion) and Rep Ranges. We’ll tackle RPE first.

Rate Of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

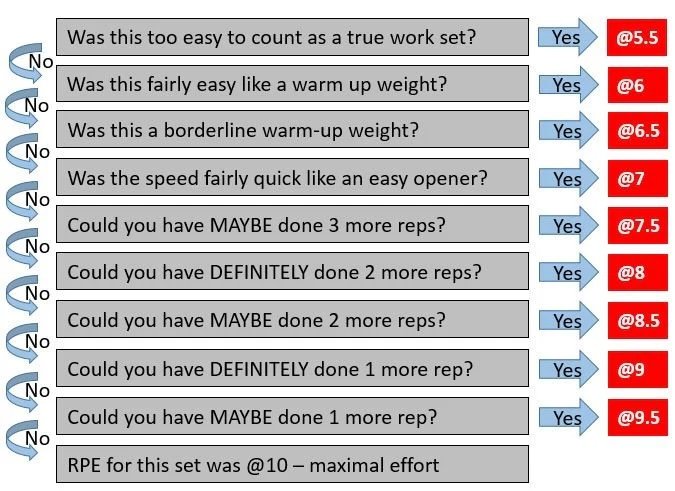

We have extensively written and talked about RPE in the MOPs and MOEs universe; however, it’s worth hitting the high notes here to better understand how this autoregulation strategy works in a double progression model. Rate of Perceived Exertion is exactly what it sounds like: how challenging did you perceive a given activity to be on some arbitrary scale (typically 1-10)? If I tell you to complete a back squat at an RPE of 8, effectively what I am asking for is that you use a weight that allows you to complete the prescribed number of reps at an intensity level that subjectively registers for you at an 8 out of 10. It might make more sense phrased thusly: an RPE 10 would be an absolute maximal effort. A quick Google search of “RPE charts” will return of plethora of options; however, the one below from Reactive Training Systems is one of the best.

Rep Ranges

The second component of our double progression model is a much less well-known tool in strength training despite having stared us in the face for generations: rep ranges. Rep Ranges are exactly what they sound like: a range of reps that are prescribed to an athlete based on the desired stimulus. For example, traditional literature holds that lifting a weight for 3-5 reps will elicit a strength-building stimulus. Most coaches, historically, will see that and choose to prescribe either 3, 4, or 5 reps depending on how intense they want the session to be. What if, instead, we prescribed the entire range and let the athlete fall within it based on how they are feeling on a given day? For an “absolute strength” stimulus, we might prescribe 1-3 reps. For more of a “hypertrophy” stimulus, we might instead choose something like 10-12 reps or even 12-15 reps. Regardless of our range and assumed stimulus, the intent for the athlete is the same: lift a weight that puts you at the desired level of intensity somewhere between the lower end and upper end of the prescribed range of reps. But how do we cage the desired level of intensity? This brings us right back to…Rate of Perceived Exertion.

Putting It Together

By combining RPE and Rep Ranges, I finally had the answer to my question of how to progress an autoregulated strength training program. Allow me to explain…

The first decision that you must make is “what is my desired stimulus on a given day?” For absolute strength, we would stick to a lower rep range such as 1-3 reps, 2-4 reps, etc. For more general strength (or even strength maintenance), we might prescribe 3-5 reps, 4-6 reps, or even 5-7 reps. Getting into more of a bodybuilding/hypertrophy stimulus would require something like 8-10, 10-12, or 12-15 reps. Finally, for muscle endurance, we might go as high as 15-20 reps for a single set.

The second decision involves the desired level of intensity. This is where RPE comes into play. I will say that for the majority of the athletes that I work with, for the majority of the time, we will stick with an RPE of 8. I find that an 8/10 intensity level is appropriate for 1) pushing close enough to a maximal effort without 2) absolutely destroying someone. If, however, we want to push intensity, we might prescribe an RPE of 9. It’s important to note, here, that a set of 3-5 reps at an RPE of 8 should require less weight than that same set of 3-5 reps at an RPE of 9. Conversely, 3-5 reps at an RPE of 7 might come into play if we’re looking more at strength maintenance or even just exposing an athlete to a new rep range or new movement following a deload week or a change in training.

Progressing Double Progression

Now that we have an understanding of how to set something like this up using rep ranges and RPE, the golden nugget is how we allow an athlete to progress from one week to the next. As a coach, here is where double progression truly shines:

We don’t need to make any changes to the prescription from one week to the next!

Stick with me. Let’s use a basic strength prescription: 3x3-5 @ RPE 8.

We now know that in this case, we would want the athlete to lift a weight that brings them to an 8 out of 10 subjective level of intensity somewhere between 3 and 5 reps. Assuming they understand RPE, that first session might return the following information:

Set 1: 225x5 @ RPE 8

Set 2: 225x5 @ RPE 8

Set 3: 225x3 @ RPE 8

What happened? It’s clear that by the third set, the athlete started to experience enough fatigue such that 5 reps at 225 would have exceeded the prescribed level of intensity (RPE 8). They could have done 5 reps; however, this would have pushed them further than we’d like to an RPE of 9 or 10. So where do we go next? Remember:

We don’t need to make any changes to the prescription from one week to the next!

For the next exposure to this session, we would leave the prescription exactly as it was previously: 3x3-5 @ RPE 8. The difference this time is that we would explain to the athlete that our goal for the session would be to use the same weight as last time and try to hit a few more reps on the third set. With that in mind, let’s assume the session returns the following information:

Set 1: 225x5 @ RPE 8

Set 2: 225x5 @ RPE 8

Set 3: 225x5 @ RPE 8

Hooray! The athlete managed to complete each set at the top end of our rep range without exceeding the desired level of intensity! At this point, as a coach, you have a few choices to make. First, you could increase the level of difficulty for the same range of reps by increasing the rate of perceived exertion. This would come across as “3x3-5 @ RPE 9”. Alternatively, you could increase the overall intensity by decreasing the rep range but keeping RPE the same. This would look like “3x2-4 @ RPE 8.” Of course, there are myriad other options as well (such as changing the exercise itself) but for the sake of simplicity, we’ll leave it with those two.

Rules of Engagement

The best part about using double progression is that there are really only two instructions that you need to give to the athlete week-on-week when they see the same prescription:

1) If you didn’t max out the rep range, use the same weight and aim for more reps

2) If you maxed out the rep range without exceeding RPE, increase the weight

Hopefully that makes sense within the context of what we now understand about RPE and Rep Ranges. In the first scenario, the athlete will have landed on the lower end of the rep range and will be experiencing progressive overload if they are able to increase the number of reps from one week to the next. In the second scenario, the athlete will have achieved the desired stimulus and is ready to increase the weight on the bar to see if they can land in that same range of reps with the same rate of perceived exertion with a heavier weight than the week before.

Closing Thoughts

As with any topic in strength and conditioning, the best we can hope for in a singular blog entry is to effectively circle a deep rabbit hole without falling in and losing ourselves in the details. There are all sorts of complexities within the context of double progression that we can tease out in future blog posts, but my goal for this initial foray is to introduce a slightly different way of thinking about training prescriptions that allow for some accounting of the actual daily readiness of the athlete. Rep ranges give us the ability to use left and right limits within which an athlete can inject their own decision-making. Similarly, RPE gives us the ability to prescribe a simple placeholder that allows for a fixed prescription to account for the athlete’s readiness on a given day. When we pair athlete autonomy with athlete readiness, we end up with a very powerful, yet simple, tool for drawing out sustainable strength training over the long term.